The world’s food supply is facing a dangerous combination of threats: war, inflation, and increasingly, drought. Across continents, dry conditions are pushing up prices on everything from coffee to beef.

In Brazil, severe drought has damaged coffee crops and driven global prices higher. The Midwestern United States has experienced years of poor rainfall, forcing ranchers to reduce cattle herds and causing beef prices to reach record levels. In China’s Yellow River Basin, which is one of its key wheat-producing regions, hot and dry weather is threatening harvests. Even Europe is feeling the strain, as drought threatens agriculture in Southern Europe and puts additional pressure on the Mediterranean diet.

The increasing concentration of food production adds to the vulnerability. Brazil and Vietnam supply most of the world’s coffee. Although wheat production is more widely distributed, major producers like Russia and Ukraine are both facing drought while also dealing with war. This combination is tightening global wheat supplies.

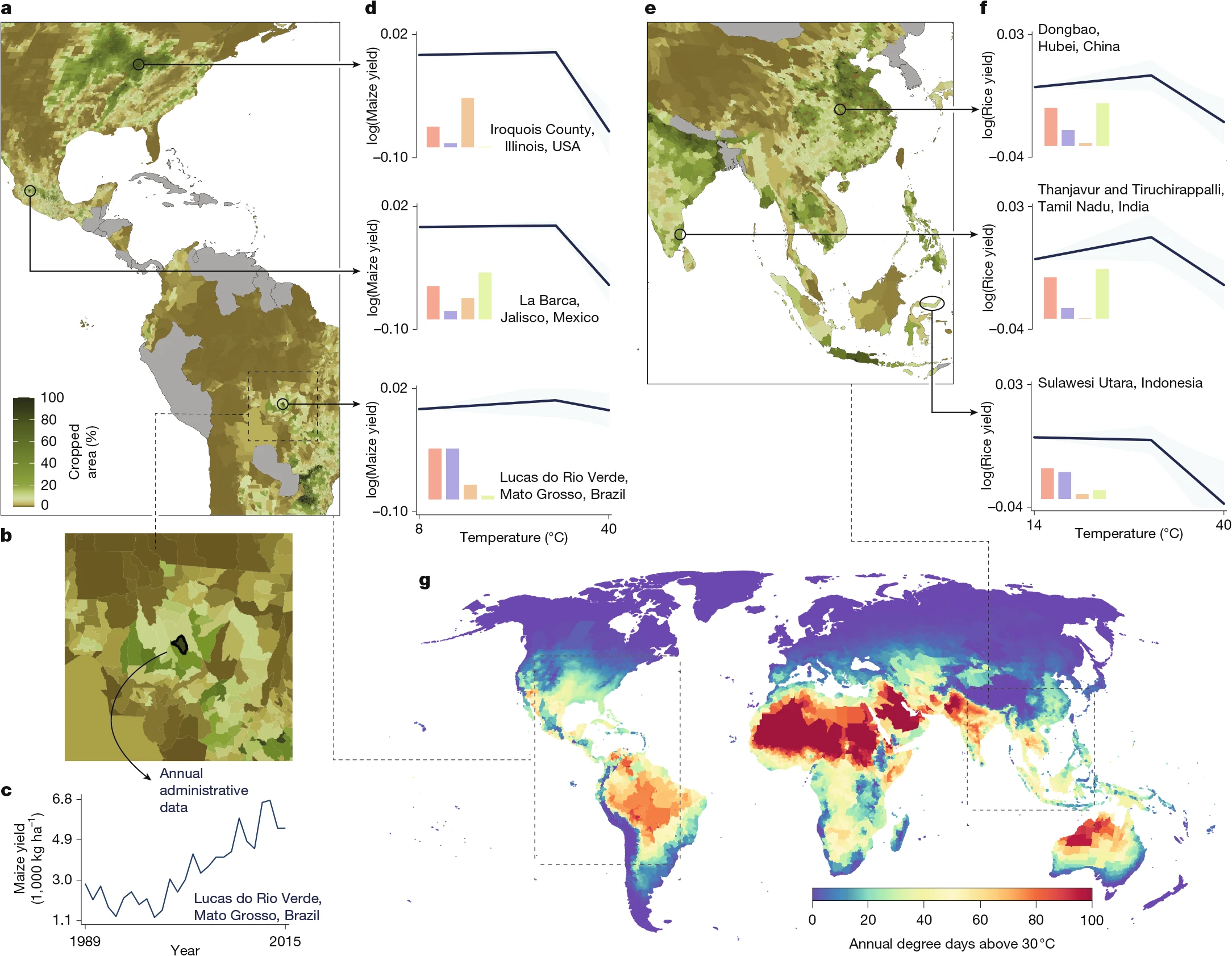

Climate change is intensifying drought patterns, leading to more frequent and severe disruptions in agriculture. Since much of the world’s calories come from just three staple grains—rice, wheat, and corn—any regional weather shocks can have global consequences.

As Somini Sengupta reports, drought is no longer a local problem. It has become a global risk to food security. Building resilience in food systems through diversified sourcing, sustainable water management, and stronger climate adaptation efforts is becoming increasingly urgent.